StratChat is a weekly virtual networking event for anyone with an interest in developing and executing better business strategies. It is an informal community-led conversation hosted by StratNavApp.com. To sign up for future events click here.

StratChat is a weekly virtual networking event for anyone with an interest in developing and executing better business strategies. It is an informal community-led conversation hosted by StratNavApp.com. To sign up for future events click here.

StratChat is conducted under Chatham House Rules. Consequently, the summary below is presented without any attribution of who said what. As such, it is an agglomerate of views - not necessarily just those of the writer or indeed of any one individual.

On 19 November 2020, we talked about the importance of storytelling in business strategy.

Storytelling provides us with two levels of insight into business strategy.

- Understanding the structure and arc of stories can help us to understand how people engage with the world on a rational as well as an emotional basis. This can help us plan the order and timing of activities with our strategy programmes.

- Using the rhetorical devices which make stories so engaging and memorable can help us to improve the way we communicate about strategy at every stage in the journey.

Segue: Last week we talked about the use of metaphors in business strategy.

In some respects, metaphors are just a simple way to tell a story. As such they are deeply ingrained in what it means to be human.

Stories convey ideas. They embody simple truths. They help to move people from one level of understanding to another. They engage more of our brains. They are more memorable. Stories are how we communicate.

We've probably been telling stories since we discovered fire and learned to sit around it at night!

And so, as business strategists, we need to be good story-tellers.

We need to be able to take people on a journey from the premise or problem to be solved, through the analysis, to the conclusions and on to action. Story-telling provides us with structures and techniques for doing so.

Story Structures

Much work has been done on the subject of story-telling. Academics have long postulated that there are only a finite number of stories that exist. They just can't agree on how many and what they are. (See 3, 6 or 36: How many basic plots are there in all stories ever written, as well as the work of Kurt Vonnegut.)

There is also a theory that all of these other story structures are just variants on a single one: The Hero's Journey.

The Hero's Journey was analysed by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 book: The Hero with the Thousand Faces.

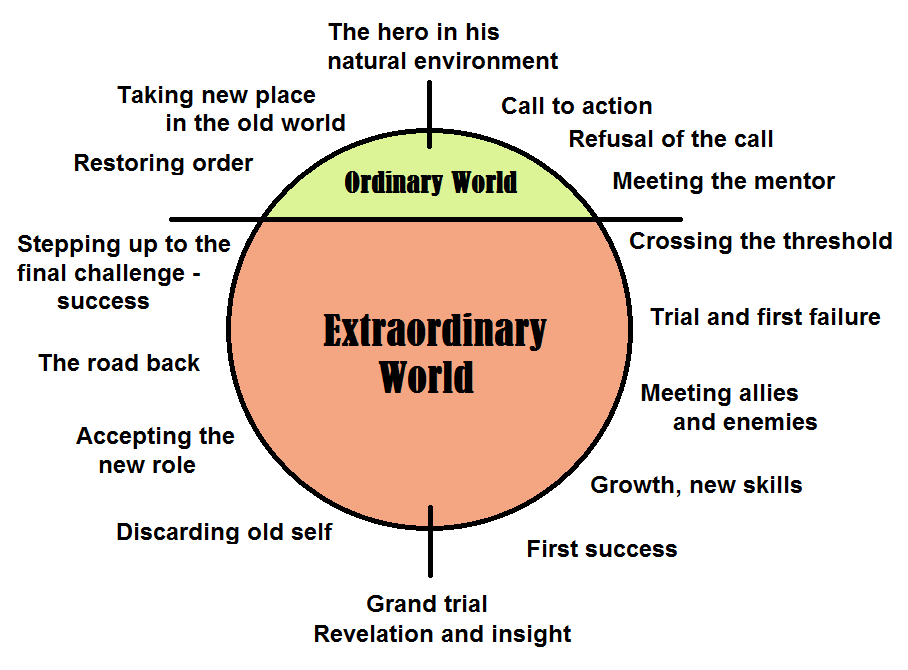

The Hero's Journey is a story about change, growth and transformation. It is described in the circular diagram to the right.

The Hero's Journey takes the hero (client firm) on a journey from the ordinary world (business as usual), through the extraordinary world of change, before returning to a new ordinary world (the improved organisation).

The Hero, in business strategy, is always the (client) organisation. And the story creates scope for different roles.

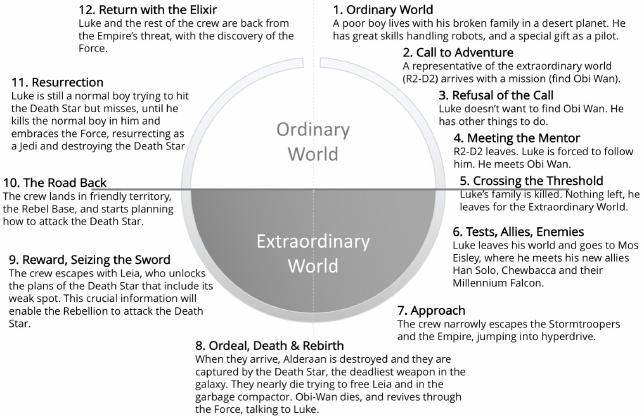

It is perhaps easiest to understand The Hero's Journey and its application if we use an example. In this case we use the film Star Wars.

As an aside, in our conversation about metaphors and the importance of distilling the essence of things. We noted that the film "Alien" had been described as "Jaws in space". Star Wars has similarly been described as "Cowboys in space". It draws heavily on the genre.

| Hero's Journey | Star Wars | Business Strategy |

| Ordinary World | Farmhand Luke Skywalker yearns for adventure. | Someone in the organisation is bothered by something, but can't necessarily put their finger on it. |

| Call to Adventure | The droids arrive bringing a taste of adventure with them. | Someone in the organisation first proposes change. |

| Refusal of the call | Luke's uncle persuades him to stay. | There is resistance to change in the organisation. |

| Meeting the mentor | Luke meets Obi-Wan Kenobi. | A new CEO, senior executive or consultant is brought in. |

| Crossing the Threshold | Luke's family is killed. There is nothing to hold him back. | A case for change is successfully made. This is the catalysts, or push for change. Sometimes it is in the form of a "burning platform". |

| Tests, Allies, Enemies | Luke is exposed to the seedy Mos Eisley, where he meets Han Solo and Chewbacca. Onboard the Millennium Falcon he starts to learn about the force. |

Stakeholder engagement, research, analysis. This is usually the most fun and interesting part of the journey where it is easiest to maintain momentum. |

| Approach | The crew escape and set off to rescue Leia. | New plans and capabilities are developed. |

| Ordeal, Death & Rebirth | Leia's rescue does not go smoothly. Obi-Wan sacrifices himself but stays talking to Luke as a Force spirit. |

Early tests/pilot programmes show that this will be harder in practice than it looked on paper. The "fun" can quickly dissipate. Around about here, the change agent has to start stepping back to let the organisation learn to do things by itself (or with less guidance). |

| Reward, Seizing the Sword | They return Leia to the rebellion. | The organisation reviews its test results to see what will/won't work at scale. Tough decisions are required. |

| The Road Back | The rebels plan to attach the death star. | Plans are laid to roll the change out across the organisation. |

| Resurrection |

The rebels attack and destroy the death star. Luke has to let go, switching off the targeting computer, and trusting his new learnings about the force. |

The changes are rolled out across the organisation. There are inevitably still unexpected costs and challenges to overcome. Crucially, the organisation has to 'let go' of past practices/power bases. |

| Return with the Elixir | The victors return and are lauded as heroes of the rebellion. Luke is no longer a farmhand. He is a Jedi. | The organisation finds its new normal and success is recognised. |

There is a brilliant video analysis of "The Matrix" using The Heros Journey available on Youtube.

The intrinsic appeal

There is an intrinsic appear in The Hero's Journey. It's something most of us relate to from childhood through to adulthood. It appeals to our desire to achieve something and to be something remarkable in our lives.

In American culture, for example, everyone loves a comeback story. This speaks to the American Dream. Hollywood stories are painted on broad canvasses and tend to be very aspirational - the characters all look like supermodels. In British culture, everyone roots for the underdog. Stories are painted on much smaller canvases, and the characters are more ordinary and relatable.

The Hero's Journey, however, provides a blueprint for hope which cuts across these cultural differences.

We want to tap into that intrinsic motivation in our strategies.

Ethos, Pathos and Logos

People, it is said, are a blend of Ethos, Pathos and Logos.

- Ethos is about character and trust.

- Pathos is about relationships and empathy.

- Logos is about reason and logic.

Successful strategies should engage all three.

Strategy models and frameworks will engage Logos. Storytelling can help us to engage Ethos and Pathos as well.

To tell a good story, you need to know your audience. Sometimes you will need to dial up the Ethos, other times the Pathos, and other times the Logos.

This will depend on the specific stakeholders you're engaging with. And their needs may vary over time. A good strategist will be able to read their audience and adjust their style to match.

The Hero's Journey story arc broadens our understanding of what it feels like to undertake strategic change. Sadly, the data tells us that many, if not most, strategies fail. They don't rescue the princess and they don't destroy the death star. The Hero's Journey helps us to see the wide variety of reasons why, and the wide variety of roles that play a role.

Sequence and Timing

The Hero's Journey helps us to understand the different processes that the hero must undertake and the different roles the mentor must play in supporting them. There is both a sequence and timing to the story. If you introduce things in the wrong order, or before the hero is ready, they may fall on deaf ears and be rejected.

If a consultant or a new leader just comes in and tells the organisation what to do, they will probably be rejected. It is necessary to first demonstrate an understanding of the challenges the organisation faces - the Pathos - and establish credibility - the Ethos - before progressing to the Logos.

In both Star Wars and The Matrix we see that the first characters to appear are C3PO, R2D2 and Trinity. These gateway characters introduce the hero to the mentor (Obi-Wan and Morpheus respectively). But in both cases, whilst the mentors are referenced early on, they don't actually appear until about 30 minutes into the story. There is a lot of ground to cover before Neo is ready to choose between the red and blue pills.

In business strategy, it can be tempting to asking senior stakeholders what they think the answer should be up front. But this is often a mistake. Once they've given their answer they subconsciously start to attach to it. It becomes harder for them to see alternatives, and even harder for them to change their minds. More junior stakeholders are also likely to be similarly swayed by what their seniors say.

So it is important to avoid asking questions which might lead to conclusions too early. We need to suspend disbelief and delay decisions until we've gathered evidence which is broad and rich enough to ensure quality outcomes.

In teaching, there are two moments of learning. The first is where someone understands something intellectually. They can recite it back and apply it in a 'classroom' situation under supervision. (Psychologist Lev Vygotsky referred to this as the Zone of Proximal Development.) The second is when the "the penny drops" and they internalise the learning. They can adapt and apply it in novel situations without supervision.

The strategist needs to understand where their stakeholders are and support accordingly. The Hero's Journey can help us to understand this pacing.

We can do this quite formally, with a Stakeholder Matrix and person-to-stakeholder marking. Or we can do it more intuitively, depending on the size and complexity of the programme.

Rhetorical devices

There are also different rhetorical techniques we can use.

For example, the BLUF method advocates that you put the Bottom Line Up Front with the supporting detail following on. This reduces the change that you'll get cut short. And if you do, at least you made your main point.

Newspapers sometimes use a similar technique. The first paragraph, in bold, summarises the whole story - the who, what, why, when, and how. Reading that alone, maybe enough to know what is going on. But if you want more detail, you can get that from the rest of the article. Editors, then work from the bottom up. The headline itself, provides an additional hook to encourage people to read that first paragraph.

In other formats, a summary is also provided. This creates a "tell them what you're going to tell them; tell them; then tell them what you told them" sandwich.

The narrative arc of a strategy is often presented as a slide deck. On technique for increasing the storytelling impact of a slide deck is:

- The slide title tells the story. Instead of simple titles like "Target Market" the slide title takes on a narrative form, such as "Our core target market of parakeet owners is growing at 7 times the rate of the population of all pet owners". Up to two lines of text is fine for a slide title.

- The slide body then presents the evidence supporting that narrative. Typically this is a chart, rather than too much text. Specific points supporting the narrative are highlighted.

- Optionally, you can also include a closer at the bottom. This drives home the narrative and typically address the "so what?" question.

In this format, readers are free to read the slide titles only. This should convey the entire narrative. If the reader accepts the narrative, they should not need to read the rest of the slide at all.

In a live environment, you also have the opportunity to not "talk beyond the close". That is, once you have presented your main point and persuaded your audience, you should stop speaking. If the audience is persuaded, there is no further value to be added. However, you could still give them cause to start to doubt their initial acceptance. So it is best to stop there (and move on to the next point if there is one). This may mean that you don't get to present all the evidence you have worked so hard to gather. But it is better not to present it than to talk past the close.

Sometimes the literal weight of the evidence is enough. When we still relied more on paper, this was conveyed by the 'thud' as the report hit the desk. Some members of the audience will be persuaded by this weight alone. It conveys the sense that the analysis is deep and therefore probably thorough and not to be challenged lightly. For some people, this is enough without actually having to review it for themselves. Again, we see this in films where the interrogator produces a fat dossier on his hapless victim. Often neither the audience nor the victim sees more than the first page.

Attendees: Chris Fox (host), Christopher Norris, Jerald Welch

Next StratChat

Next week, on Thursday 26 November 2020 we will be picking up the thread with a conversation about evidence. Why not join us? We'd love to add your anecdotes, perspective and question to the conversation!