StratChat is a weekly virtual networking event for anyone with an interest in developing and executing better business strategies. It is an informal community-led conversation hosted by StratNavApp.com. To sign up for future events click here.

StratChat is a weekly virtual networking event for anyone with an interest in developing and executing better business strategies. It is an informal community-led conversation hosted by StratNavApp.com. To sign up for future events click here.

StratChat is conducted under Chatham House Rules. Consequently, the summary below is presented without any attribution of who said what. As such, it is an agglomerate of views - not necessarily just those of the writer or indeed of any one individual.

On 21 January 2021, we talked about Scenario Planning.

Prediction versus Anticipation

Most of us recognise that we can't predict the future.

Unfortunately, many people stop there. If you can't predict the future, then there is no point in worrying about it.

Whilst you can't predict the future, you can anticipate it.

And when you start to anticipate the future, you realise that you probably need to anticipate multiple futures.

For example, if you flip a coin, you can't predict how it will land. But you can anticipate that it will almost certainly land on heads or on tails. (In theory, it could also land on the edge. But you'd probably discount that as a likely option.)

Options versus Scenarios

We use the word 'options' to describe the choices we face.

If we could choose to do A or B or C, then we'd describe A, B and C as options. Similarly, if we could choose to do A or not to do A, then we'd describe A as an option.

In contrast, we use the word 'scenarios' to describe futures which we can anticipate but over which we have little control. In our coin flip example, we would anticipate two scenarios: heads or tails.

The Cone of Uncertainty

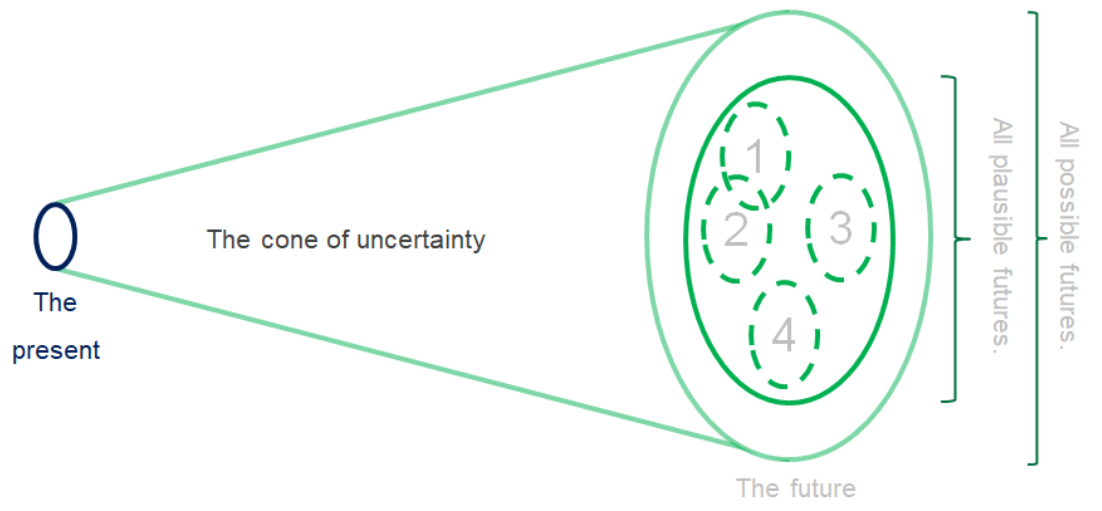

The cone of uncertainty provides us with a way to visualise how scenarios work.

The cone of uncertainty provides us with a way to visualise how scenarios work.

It is harder to know what the future might hold than it is to understand the present. We know more about the present than we do about the future. We are less uncertain about the present than we are about the future.

Obviously, we can't know everything about the present, and there is still some uncertainty in the present.

And so we represent the future as a smaller circle and the future as a larger circle. The further into the future we try to look, the more the uncertainty and so the larger the size of the circle. This creates the cone effect.

Of course, this is a concrete representation of an abstract concept. In reality, there are no clear or straight lines. But we imagine them in order to understand the concept.

At any future time, we can anticipate all possible future outcomes. But the range of possible futures is very quickly too much to contemplate. So we look for ways to make the future easier to process.

We can do two things:

- We can dismiss possible futures which are not useful. For example, we might consider that the total destruction of life on earth through global thermo-nuclear warfare or a large meteorite strike is at least a possibility. But, at least as far as most business strategies are concerned, there is probably nothing you can do about it. So we might exclude that from further consideration. That reduces the scope of our consideration from the larger to the smaller circle representing the futures under consideration.

- We can choose a smaller number of representative futures from within the space that remains. These are represented by the dotted-line circles numbered 1 to 4 on our diagram. These become our scenarios, and provide the focus of the rest of the discussion.

Notice that the scenarios don't include the entirety of the future space under consideration. However, it is important that they are widely enough spread to at least get close to as much of the possible space as possible. It is also possible that they overlap slightly.

There is also no right or wrong number of scenarios to consider. About 4 seems about right. Too many fewer and you will probably struggle to provide enough variety in your scenarios to be useful. Too many more and you risk getting lost in the weeds.

Because you will choose a limited number of scenarios to work with, it is quite probable that what actually happens won't exactly match any of your scenarios. That is, that the actual future squeezes through one of the gaps between your scenarios. This does not invalidate the exercise. Even in this circumstance, you will still be better prepared for what does happen than if you had done nothing.

Actually coming up with the right set of scenarios is as much an art as it is a science. The only real criteria are:

- how useful they are for your strategy process, and

- how much of a surprise whatever eventually does happen comes as.

Techniques for building scenarios

But there are some techniques that can make it easier to develop useful scenarios. One is as follows:

But there are some techniques that can make it easier to develop useful scenarios. One is as follows:

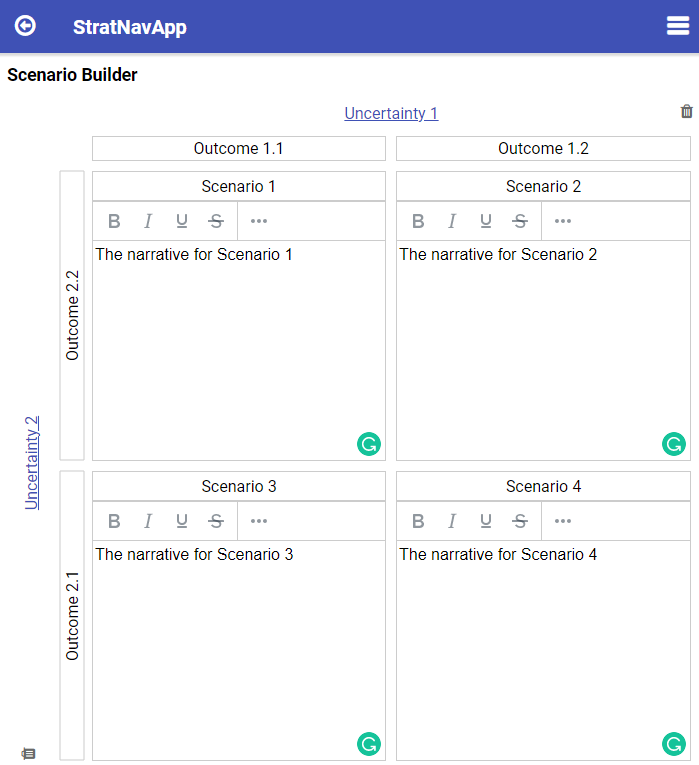

- Start by choosing the two things about the future, as it relates to the business, that you are least certain about. It helps if the two things are very independent of each other. For example, if you're a travel company, you could be very uncertain as to whether or how quickly business travel returns to pre-pandemic levels. If you've done a PESTEL analysis, or the Opportunities and Threats in a SWOT analysis, you could look for ideas there.

- For each of the two uncertainties, come up with (at least) two clearly distinctive outcomes. In our travel company example, these could be that (a) business travel recovers slowly and does not return to pre-pandemic levels within the next 5 years or (b) business travel bounces back to pre-pandemic levels within a year and then continues to grow.

- From 2 uncertainties each with 2 outcomes, you can create a 2X2 matrix. Each cell in the 2X2 matrix becomes a scenario with its own title and narrative. You can see an example of what this might look like in the diagram above/to the right.

- Scenarios should have short but memorable titles.

- Scenario narratives are typically about a page long. They should be based around the relevant outcome pairs for the two uncertainties collected but should be supplemented by specifics from across all your relevant situational (company, industry and competitor) analyses.

- Both the scenario title and narrative should aim to engage and challenge readers at both a rational and emotional level.

This 2X2 matrix is merely a technique to help you build useful scenarios. It is not a hard and fast rule. You could have 3 outcomes for either of the uncertainties. This could yield a 3X2 or even 3X3 matrix. You don't need to write a scenario for every cell on the matrix. And, of course, you can create additional scenarios without using this technique at all.

Evaluating options against scenarios

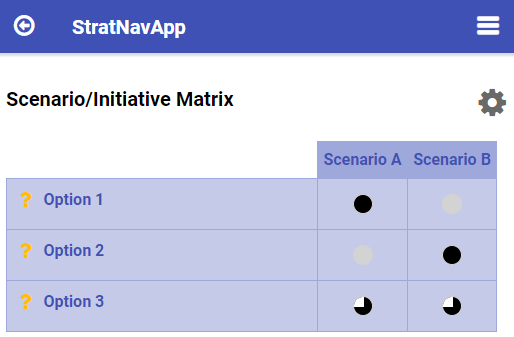

Once you developed your scenarios, you can include them in your processes for selecting and prioritising options.

As a general rule, options which produce good outcomes across a wide range of scenarios are better than options which produce good outcomes against some scenarios and bad outcomes against others.

For example, in the diagram to the right, whilst option 1 produces the best outcome under scenario A and option 2 produces the best outcome under scenario B, option 3 would be prefered as it produces good outcomes in both scenarios. This is despite the fact that option 3 never produces an outcome as good as what option 1 or 2 could produce. We would describe option 3 as being more robust in the face of future uncertainty than either option 1 or option 2.

For example, in the diagram to the right, whilst option 1 produces the best outcome under scenario A and option 2 produces the best outcome under scenario B, option 3 would be prefered as it produces good outcomes in both scenarios. This is despite the fact that option 3 never produces an outcome as good as what option 1 or 2 could produce. We would describe option 3 as being more robust in the face of future uncertainty than either option 1 or option 2.

Of course, this robustness would be factored in with all the other factors you would use in selecting and prioritising options.

Option 3 is what might sometimes be called a "no regret" or a "least regret" option.

Options 1 and 2 would not necessarily be dismissed out of hand. However, you might choose to defer them until it became more apparent which of the two scenarios the world was moving towards. This requires ongoing monitoring of your scenario analysis.

Ongoing monitoring

In addition to using your scenarios to evaluate options, you can also use them to identify exactly which signals from the competitive environment you should be monitoring.

This can help you to cut through the noise and focus on the signals that will provide the most insight about:

- how the situation is evolving and

- what the impact could be on the organisation and its strategy.

Other techniques for dealing with uncertainty

There are, of course, many other techniques that you can use for dealing with uncertainty.

- Wargaming is a technique for practising how you would respond to some future event. Wargaming works best where the event is sudden. Also, it is usually used for negative events. A fire-drill is a good example of wargaming, even if it is quite simple - you practice how the organisation will respond if a fire breaks out. Scenario planning, in contrast, is better suited towards both positive or negative outcomes which unfold over a period of time.

- Monte Carlo Simulation is a technique whereby you feed randomised inputs into a complex mathematical model. If you do this many times - usually thousands of times - you can observe the range and probabilities of outcomes. Eventually, you can infer a probability distribution for the outcomes. Monte Carlo Simulations work well for situations which can be mathematically modelled. Scenarios work where it is difficult to determine the exact inputs or precisely model the mathematics for translating them into outputs. Monte Carlo Simulation is limited to quantifiable variables, whilst scenarios can also include more qualitative factors.

- Game Theory is a technique for modelling the responses of other market participants to an organisation's strategic moves or other events. The other participants are typically competitors, but could also be customer, regulators or any other players. Such models can be used to determine optimal outcomes. Like Monte Carlo Simulation, Game Theory relies on the quantification of all outcomes and probabilities.

- Real Options give organisations the right but not the obligation to undertake a certain business opportunity or investment. These could be linked to scenario outcomes.

If we consider the Cynefin domains, we might argue that scenarios come into their own as you approach the 'chaotic' domain. Or at least where cause and effect become difficult to quantify.

Drawing inspiration from science fiction

In constructing scenarios, we can draw inspiration from science fiction writers. The British TV series Black Mirror provides a great example. Each story:

- takes an aspect of modern society that we already understand (in Black Mirror this usually involves technology in some way, but that does not need to be the case),

- extrapolates it in one direction into the future,

- builds a rich picture of what the world might be like were that to come to pass,

- constructs a story in which the characters experience that world and its consequences.

Science fiction writers tend towards dystopian futures. Those are futures we'd rather avoid. Perhaps that is because dystopian futures sell more books and films.

Before COVID-19 we also saw a number of works of fiction which imagined what a global pandemic might be like. These include Contagion and Outbreak are well-known examples. What actually happened with COVID-19 has been different to what happened in those films. But those films did still help to shape the way we think about pandemics in general.

As strategists, we could take a more objective approach and include both positive and negative outcomes.

What is good about these stories is that the transcend quantitative analysis and engage our rational and emotional beings. They also help to provide context around the broader impact that could unfold.

Computer games

Similarly, we have seen computer games which allow us to simulate the effects of, say, a pandemic or global warming. Again, these help us to increase our understanding of how something might unfold. And they allow us to practise our response (see Wargaming above).

Before we had computer games, we had other games and simulations. These were often used as teaching aids. The use of computers, however, makes these much richer.

Even so, their effectiveness is limited by how well they've been programmed. And computer programmes are limited by our ability to quantify and mathematically model the outcomes.

So, whilst they may be very effective at increasing, within bounds, our rational understanding, they're unlikely to provide as much context and be quite as broadly engaging as science fiction can be.

Scenarios in everyday life

We use the concepts in scenario planning all the time in everyday life.

For example, when playing golf. We may find ourselves in a position where, if we play the shot well, we can reach the green. But if we slice it, we may end up deep in the trees. Our scenarios are (a) we hit a good shot or (b) we slice it. Our level of control over those outcomes is limited by our skill as a golfer. Our options are (1) aim for the green or (2) play it safe and lay up. We make such evaluations all the time.

This story of a professor talking to a French cafe owner shows how this simplicity can translate into business as well.

However other times, the evaluation becomes more complex. This is particularly when:

- the scenarios and options themselves are more complex,

- the organisations dealing with them become more complex, in terms of their structures, products and services, etc, and

- we are dealing with a wider range of decision-makers with different perspectives.

It is when this happens, that we need to be more formal and structured in our approach to scenario planning.