StratChat is a weekly virtual networking event for business strategists and anyone with an interest in developing and executing better business strategies. It is an informal community-led conversation hosted by StratNavApp.com. To sign up for future events click here.

StratChat is a weekly virtual networking event for business strategists and anyone with an interest in developing and executing better business strategies. It is an informal community-led conversation hosted by StratNavApp.com. To sign up for future events click here.

StratChat is conducted under Chatham House Rules. Consequently, the summary below is presented without any attribution of who said what. As such, it is an agglomerate of views - not necessarily just those of the writer or indeed of any one individual.

This week's conversation looked at some of the main causes why business strategies don't get executed.

1. Inexecutable Strategies

Some strategies are just not that well-formulated. Some may even be inexecutable.

There are four subcategories of inexecutable strategies.

a. Strategies which are at best lofty ideals or outcomes with no way specified of achieving them.

For example, a company may say that their strategy is to be number one or number two in every industry in which they compete. This may be a great ambition. But it's not a strategy. It gives you no indication of what it will take to become number one or number two, or of what the company will do to achieve that.

An explanation sometimes given for such strategies is that the leader's role is to set the vision and then leave it to their team to work out how to achieve it. This means that the leader has delegated responsibility for setting the strategy to others within the organisation. If the organisation is able to work together to develop and execute a strategy, or if another person steps forward to fill that leadership role, this can work. However, it is more likely to lead to

- complete abdication of the strategy role and no strategy being developed and executed at all, or

- multiple conflicting strategies and infighting.

b. Strategies which are really just last year's budget plus 10%.

Again, there is not really a strategy here, other than to encourage everyone to work harder and hope things go well.

c. Strategies which are too exclusively far-term.

These paint a clear picture of what the organisation will need to do in 5 or 10 years time. But they don't provide any detail on what the organisation needs to do right now to help it prepare for and move towards that place. People may be really bought into the long term future, but they don't know what to do about it now. As a result, they wait. Or they work on things which are impractical because they are too detached from the organisation's current reality.

The 3 Horizons model is a great tool for helping organisations to find the right balance between short, medium and longer-term priorities.

It is said that we overestimate how quickly the world will change in the short term and underestimate how much it will change in the long term. One way to try to overcome this is to remember how different the world as 5 or 10 years ago, and then image that it will be as different again in 5 to 10 years time. For example, you can look at the companies, products and services which we now take for granted and remind yourself when they first came to market.

(Having too much focus on the near term and not enough on the longer-term is equally bad. However, at least it is likely to get done, even if what is done is not enough to secure the organisation's long-term success.)

d. Strategies which are insufficiently detailed and/or out of date.

A lot of people think they are strategists. For example, many startup founders include a strategy in their pitch decks, and then proceed on the basis that strategy is 'done'. But such strategies are often superficial and quickly become out of date. For others, strategy is an event - a moment in time - rather than a continual process and a way of running the business. Or perhaps they outsource strategy to a consultant but then fail to internalise the result.

2. Poor communication

It doesn't matter how good your strategy is, if you don't tell people what it is they can't execute it!

But you need to do more than tell them what it is and also tell them why it is that. That will help them to buy into it, internalise it, and execute it in a consistent manner. People are much more likely to be motivated by a strategy if it is presented as a clear and positive choice with an explanation of why that choice is better than the alternative choices which could have been made.

It's probably impossible to communicate your strategy too much. If you are very close to it, and/or were involved in crafting it, it may be close to your heart. But other people have all sort of other distractions. The more often they hear the message the more likely they are to remember and take it on board.

Regardless of how much you communicate your strategy, if it is not simple and memorable enough, most of it will get lost. The Strategy House is very useful for doing this. Three or four clearly connected messages are ideal for describing a strategy. If you try and boil it down to only one central idea, it's hard to convey any logical and reinforcing connections. If you have only two ideas, its easy for them to end up appearing to compete with each other for primacy. Three ideas are able to balance each other out whilst reinforcing each other at the same time.

A stool with one or two legs will be unstable. A three-legged stool will be stable. Four legs are also good although not strictly necessary. Any more than 4 legs is adding complexity for little or no benefit. The same logic applies when distilling and communicating the essence of a strategy.

Another good technique for communicating strategy is to identify a "burning platform". Most people are naturally resistant to change. They prefer the status quo. A burning platform provides a reason why change is necessary; why the status quo is undesirable. A burning platform can be internal. For example, if the business is losing money and facing bankruptcy with the loss of jobs. Or it can be external. For example, if some technological change or competitor is threatening to make your current business less attractive.

For most startups, the decision is even simpler. With no cashflow from existing business, they must either execute the strategy or perish.

3. Poor enablement

Once your strategy is well formulated and properly communicated, the next challenge is to enable the organisation to deliver. That is, to create the conditions within the organisation under which delivery is possible.

The first challenge is change fatigue. If you've had too many strategic changes - or other changes - people just get worn out. They start craving a little stability. And their appetite for absorbing new change is sated.

Even without change fatigue, the daily pressures of business-as-usual can also crowd out organisations' capacity to execute strategy. People can be so busy focusing on the day-to-day and fighting fires that they no longer have time to focus on the longer term more strategic issues. For many businesses, it is feast or famine:

- feast: if you're busy because business is booming, then you need to make hay while the sun shines. There is little time left to worry about strategy.

- feast: if, on the other hand, business isn't booming, then you're probably too busy fighting fires and trying to drum business up to have any time left to focus on strategy.

COVID-19 provides a great example. It's clear the world is changing, and therefore there is a great need to respond strategically. But the nature of the crisis is that people have been battling to stay afloat and just haven't had the bandwidth.

This is a great selling point for consultants. CEOs and their business-as-usual teams don't always have the time. So they hire consultants to provide them with the extra bandwidth (and skill).

A problem with many new strategies is that they are simply added on top of business as usual activity. They suggest many new additional things that the organisation needs to do, but they don't suggest what the organisation should stop doing in order to create capacity to do those new things. That is why it is as important for a strategy to outline what must be done as it is to outline what should not be done.

But it is not just about capacity. Capability should also be considered. A strategy should consider:

- what tools will the organisation need to achieve the strategy, and what investment is required to build, buy or rent those tools.

- what organisation structure will best implement the accountabilities and decision making channels to allow people to execute the strategy effectively.

One of the biggest barriers to strategy is habit. Habits are a very powerful force in favour of inertia. They take time and effort to change. If you don't invest the effort and allow the time for them to change, then people will inevitably rever to what they were doing before and your strategy will fail.

Again, COVID-19 provides an interesting example. The lockdown has been long enough that people will have developed new habits. When the lockdown is lifted, it will require effort to change those habits. Alternatively, if those new habits are considered useful, they will present an opportunity that organisations can leverage.

4. Political challenges

Anecdote: A mid-tier executive approached their organisation's internal strategy team hoping to get support for a project they were proposing. The strategy asked how this project was aligned with the organisation's strategy. The executive replied that it probably didn't, but they wanted to do it anyway as it would be great for their career.

Not everyone is a team player. Decision-makers have vested interests and biases. Some of them will pursue those vested interests independently of the strategy and despite the inherent conflicts. Sometimes, they will also try and co-opt and bend a strategy to better suit their own interests.

There exists an agency problem in business. This occurs when decision-makers are spending other people's money. Some people are good agents and will act in the best interests of the people whose money it is. Other people are not good agents and will act in their own self-interest.

These problems are accentuated when organisations are under-resourced and things become more difficult. Sometimes, you get off to a good start, but then culture and habits start to kick in and old behaviours re-emerge.

5. Misaligned incentives

We discussed KPIs and incentives at length at StratChat on 20 August.

In addition to that, you have the problem of organisations getting too focused on short-term targets such as quarterly earnings reports to the stock market, or monthly sales targets, etc. Given the choice to focus on those short terms targets rather than on the longer-term strategy, it is understandable that people will choose the former.

Similarly, some organisations also distinguish between operational scorecards and metrics and strategic scorecards and metrics, instead of integrating them. Again, this can force individual actors to have to choose between the two.

6. Too top down

Business strategy must involve an element of top-down decision making if it is to achieve a single unified strategy for the organisation. But that does not mean that bottom-up does not have a role to play.

Team members are much more likely to be motivated to deliver a strategy if they feel that they had had some role, no matter how small, in choosing it. People are naturally resistant to autocracy.

7. Change

If your strategy is too static and not responsive to changing circumstances it will become harder to execute as time goes by. On the other hand, if you change it too often, people will get change fatigue.

Another factor is a change in leadership. This often results in a change in strategy - meaning that the old strategy is abandoned before it is executed.

This can be a good thing. For example, if the board has lost confidence in the old leadership because the old leadership's strategy was not delivering the results. Then, they might bring in new leadership with the express purpose of developing a new strategy.

However, it can also be a bad thing. For example, if the existing strategy is working but one or more leaders are replaced because the old ones retired, were promoted or changed jobs. Then, the new leader may decide to develop a new strategy to 'put their own stamp on things' or to 'make their mark'. This can be a decision more driven by the new leader's ego than any fundamental underlying change.

8. Not enough follow-through

Many strategies are quite long term. Some can take 5 to 10 years play out. These require up-front investment, conviction and discipline to see them through. There will inevitably be short term losses and sacrifices.

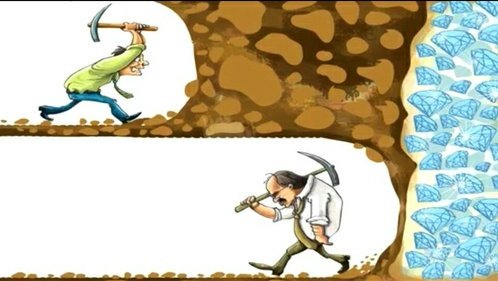

Sometimes people just give up too quickly. This is particularly a risk if there is a change of leadership or funding.

Startups are also particularly vulnerable to this because they don't have other revenue streams to carry them through (before they run out of cash), or where the original founders' influence and vision are diluted as the organisation grows.

Again, COVID-19 provides an example. If you set up your startup 6 months before COVID struck and pulled the rug out from under your startup, do you:

- accept defeat and give up, or

- recognise that the underlying vision and mission remain sound and that COVID-19 is only a temporary setback?

That second choice may mean that things will take longer. And it also requires a deeper level of conviction to enable you to endure the short and medium-term setbacks.

Many founders don't give this enough consideration ahead of time. They are too focused on building the business and selling. However, investors are more concerned about what might go wrong.

Most people struggle enough to imagine what one future might hold for their business. Many also struggle to know what to do with the idea that some future event may or may not happen. They want to choose and plan for one outcome or the other. But what strategy really needs is for people to imagine multiple possible futures. Scenario planning provides a framework for doing this.

Giving due consideration to multiple possible futures is also a great tool for building trust with customers, investors or partners. It leads to richer conversations, less conflict where different people see different futures, and fewer relationship disrupting surprises!

Some discussions about the nature of strategy

We discussed some definitions and concepts during the course of the conversation, such as:

- A strategy is a plan, consisting of a set of interconnected and optimised decisions, to achieve an overarching goal.

- You can have a strategy for achieving a personal goal (like losing weight or completing an ultramarathon), for winning a game, or for your business, etc.

- Each of these different contexts produces different complexities. For example, one of the complexities in business strategy is that your competitors are fighting back at the same time as you are executing your strategy. Regulators, customers, etc. are also always changing. That is one of the reasons why strategy must be continually responding and adjusting to the external world. Game theory will get you some of the way but it quickly becomes too complex. In software development terms, business strategy is more like an Agile project than a waterfall project.

- Dwight Eisenhower said that "plans are nothing, planning is everything". The advantage of having a plan is that when something happens, it makes it easier to see if it was something you had anticipated or not. If you had anticipated it, then everyone already knows how you will respond. If you have not anticipated it, then everyone knows that its time to consider whether or not you need to adjust the strategy. So you can reach decisions to adjust to unknowns and changes in the external world much more quickly.

Attendees: Chris Fox (host and notes), Azfar Haider, Christopher Sable and Pratap Lakshmanan

Future topics

Some topics proposed for future StratChats include:

- How do you know when its time to stick with your existing strategy or its time to change it.

- Design thinking and strategy.

- The fractal nature of strategy - strategy in large versus small organisations, and how deep to go.

So don't forget to sign up to join us!

We will have a StratChat next week on Thursday 10th. We will then skip the week of Thursday 17 September, and resume on Thursday 24 September.